Clearly and unambiguously communicate computational ideas using appropriate formalism. Translate across levels of abstraction.

Translating between symbolic and English versions of statements using precise mathematical language

Using appropriate signpost words to improve readability of proofs, including ‘arbitrary’ and ‘assume’

Know, select and apply appropriate computing knowledge and problem-solving techniques. Reason about computation and systems. Use mathematical techniques to solve problems. Determine appropriate conceptual tools to apply to new situations. Know when tools do not apply and try different approaches. Critically analyze and evaluate candidate solutions.

Judging logical equivalence of compound propositions using symbolic manipulation with known equivalences, including DeMorgan’s Law

Writing the converse, contrapositive, and inverse of a given conditional statement

Determining what evidence is required to establish that a quantified statement is true or false

Evaluating quantified statements about finite and infinite domains

Apply proof strategies, including direct proofs and proofs by contradiction, and determine whether a proposed argument is valid or not.

Identifying the proof strategies used in a given proof

Identifying which proof strategies are applicable to prove a given compound proposition based on its logical structure

Carrying out a given proof strategy to prove a given statement

Carrying out a universal generalization argument to prove that a universal statement is true

Using proofs as knowledge discovery tools to decide whether a statement is true or false

Review quiz based on Week 5 class material (due Monday 02/09/2026)

Midquarter feedback: please let us know what’s working well for you and what isn’t. https://canvas.ucsd.edu/courses/71479/quizzes

Homework 3 due on Gradescope https://www.gradescope.com/ (Thursday 02/12/2026)

Review quiz based on Week 6 class material (due Monday 02/16/2026)

No class Monday of Week 7 (02/16/2026) in observance of UCSD holiday.

We now have propositional and predicate logic that can help us express statements about any domain. We will develop proof strategies to craft valid argument for proving that such statements are true or disproving them (by showing they are false). We will practice these strategies with statements about sets and numbers, both because they are familiar and because they can be used to build cryptographic systems. Then we will apply proof strategies more broadly to prove statements about data structures and machine learning applications.

Addition and multiplication of real numbers are each commutative and associative.

The product of two positive numbers is positive, of two negative numbers is positive, and of a positive and a negative number is negative.

The sum of two integers, the product of two integers, and the difference between two integers are each integers.

For every integer \(x\) there is no integer strictly between \(x\) and \(x+1\),

When \(x, y\) are positive integers, \(xy \geq x\) and \(xy \geq y\).

Definition: When \(a\) and \(b\) are integers and \(a\) is nonzero, \(a\) divides \(b\) means there is an integer \(c\) such that \(b = ac\) .

Symbolically, \(F(~(a,b)~) = \phantom{\exists c\in \mathbb{Z}~(b=ac)}\) and is a predicate over the domain

Other (synonymous) ways to say that \(F(~(a,b)~)\) is true:

\(a\) is a factor of \(b\) \(a\) is a divisor of \(b\) \(b\) is a multiple of \(a\) \(a | b\)

When \(a\) is a positive integer and \(b\) is any integer, \(a | b\) exactly when \(b \textbf{ mod } a = 0\)

When \(a\) is a positive integer and \(b\) is any integer, \(a | b\) exactly when \(b = a \cdot (b \textbf{ div } a)\)

Translate these quantified statements by matching to English statement on right.

2 \(\exists a\in \mathbb{Z}^{\neq 0} ~(~F(~(a,a)~)~)\)

\(\exists a\in \mathbb{Z}^{\neq 0} ~(~\lnot F(~(a,a)~)~)\)

\(\forall a\in \mathbb{Z}^{\neq 0} ~(~F(~(a,a)~)~)\)

\(\forall a\in \mathbb{Z}^{\neq 0} ~(~\lnot F(~(a,a)~)~)\)

Every nonzero integer is a factor of itself.

No nonzero integer is a factor of itself.

At least one nonzero integer is a factor of itself.

Some nonzero integer is not a factor of itself.

Claim: Every nonzero integer is a factor of itself.

Proof:

Prove or Disprove: There is a nonzero integer that does not divide its square.

Prove or Disprove: Every positive factor of a positive integer is less than or equal to it.

Claim: Every nonzero integer is a factor of itself and every nonzero integer divides its square.

Definition: an integer \(n\) is even means that there is an integer \(a\) such that \(n = 2a\); an integer \(n\) is odd means that there is an integer \(a\) such that \(n = 2a+1\). Equivalently, an integer \(n\) is even means \(n ~\textbf{ mod }~2 = 0\); an integer \(n\) is odd means \(n ~\textbf{ mod }~2 = 1\). Also, an integer is even if and only if it is not odd.

Definition: An integer \(p\) greater than \(1\) is called prime means the only positive factors of \(p\) are \(1\) and \(p\). A positive integer that is greater than \(1\) and is not prime is called composite.

Extra examples: Use the definition to prove that \(1\) is not prime, \(2\) is prime, \(3\) is prime, \(4\) is not prime, \(5\) is prime, \(6\) is not prime, and \(7\) is prime.

True or False: The statement “There are three consecutive positive integers that are prime."

Hint: These numbers would be of the form \(p, p+1, p+2\) (where \(p\) is a positive integer).

Proof: We need to show

True or False: The statement “There are three consecutive odd positive integers that are prime."

Hint: These numbers would be of the form \(p, p+2, p+4\) (where \(p\) is an odd positive integer).

Proof: We need to show

At this point, we’ve seen the proof strategies

2

A counterexample to prove that \(\forall x P(x)\) is false.

A witness to prove that \(\exists x P(x)\) is true.

Proof of universal by exhaustion to prove that \(\forall x \, P(x)\) is true when \(P\) has a finite domain

Proof by universal generalization to prove that \(\forall x \, P(x)\) is true using an arbitrary element of the domain.

To prove that \(\exists x P(x)\) is false, write the universal statement that is logically equivalent to its negation and then prove it true using universal generalization.

To prove that \(p \land q\) is true, have two subgoals: subgoal (1) prove \(p\) is true; and, subgoal (2) prove \(q\) is true. To prove that \(p \land q\) is false, it’s enough to prove that \(p\) is false. To prove that \(p \land q\) is false, it’s enough to prove that \(q\) is false.

Proof of conditional by direct proof

Proof of conditional by contrapositive proof

Proof of disjuction using equivalent conditional: To prove that the disjunction \(p \lor q\) is true, we can rewrite it equivalently as \(\lnot p \to q\) and then use direct proof or contrapositive proof.

Proof by cases.

Recall the definitions: The set of RNA strands \(S\) is defined (recursively) by: \[\begin{array}{ll} \textrm{Basis Step: } & \texttt{A}\in S, \texttt{C}\in S, \texttt{U}\in S, \texttt{G}\in S \\ \textrm{Recursive Step: } & \textrm{If } s \in S\textrm{ and }b \in B \textrm{, then }sb \in S \end{array}\] where \(sb\) is string concatenation.

The function rnalen that computes the length of RNA strands in \(S\) is defined recursively by: \[\begin{array}{llll} & & \textit{rnalen} : S & \to \mathbb{Z}^+ \\ \textrm{Basis Step:} & \textrm{If } b \in B\textrm{ then } & \textit{rnalen}(b) & = 1 \\ \textrm{Recursive Step:} & \textrm{If } s \in S\textrm{ and }b \in B\textrm{, then } & \textit{rnalen}(sb) & = 1 + \textit{rnalen}(s) \end{array}\]

The function basecount that computes the number of a given base \(b\) appearing in a RNA strand \(s\) is defined recursively by: \[\begin{array}{llll} & & \textit{basecount} : S \times B & \to \mathbb{N} \\ \textrm{Basis Step:} & \textrm{If } b_1 \in B, b_2 \in B & \textit{basecount}(~(b_1, b_2)~) & = \begin{cases} 1 & \textrm{when } b_1 = b_2 \\ 0 & \textrm{when } b_1 \neq b_2 \\ \end{cases} \\ \textrm{Recursive Step:} & \textrm{If } s \in S, b_1 \in B, b_2 \in B &\textit{basecount}(~(s b_1, b_2)~) & = \begin{cases} 1 + \textit{basecount}(~(s, b_2)~) & \textrm{when } b_1 = b_2 \\ \textit{basecount}(~(s, b_2)~) & \textrm{when } b_1 \neq b_2 \\ \end{cases} \end{array}\]

Which proof strategies could be used to prove each of the following statements?

Hint: first translate the statements to English and identify the main logical structure.

\(\forall b \in B~\exists s \in S~(~basecount(~(s,b)~)~ > 0~)\)

\(\exists s \in S~\forall b \in B~(~basecount(~(s,b)~)~ > 0~)\)

\(\exists s \in S \, (\textit{rnalen(s)} = \textit{basecount}(~(s, \texttt{A})~)\)

\(\forall s \in S ~\exists b\in B ~(~basecount(~(s,b)~) > 0~)\)

\(\forall s \in S \, (\textit{rnalen(s)} \geq \textit{basecount}(~(s, \texttt{A})~))\)

\(\forall s \in S~(~rnalen(s) > 0~)\)

Claim \(\forall s \in S ~(~rnalen(s) > 0~)\)

Proof: Let \(s\) be an arbitrary RNA strand. By the recursive definition of \(S\), either \(s \in B\) or there is some strand \(s_0\) and some base \(b\) such that \(s = s_0 b\). We will show that the inequality holds for both cases.

\(\phantom{Basis}\) Case: Assume \(s \in B\). We need to show \(rnalen(s) > 0\). By the basis step in the definition of \(rnalen\), \[rnalen(s) = 1\] which is greater than \(0\), as required.

\(\phantom{Recursive}\) Case: Assume there is some strand \(s_0\) and some base \(b\) such that \(s = s_0 b\). We will show (the stronger claim) that \[\forall u \in S ~\forall b \in B ~( ~\textit{rnalen}(u) >0 \to \textit{rnalen}(ub) >0 ~)\] Consider an arbitrary RNA strand \(u\) and an arbitrary base \(b\), and assume towards a direct proof,\(~~{\phantom{ this is the induction hypothesis}}~~\) that \[rnalen(u) > 0\] We need to show that \(rnalen(ub) > 0\). \[rnalen(ub) = 1 + rnalen (u) > 1 + 0 = 1 > 0\] as required.

Claim \(\forall s \in S \, (\textit{rnalen(s)} \geq \textit{basecount}(~(s, \texttt{A})~))\):

Proof: We proceed by structural induction on the recursively defined set \(S\).

Basis Case: We need to prove that the inequality holds for each element in the basis step of the recursive definition of \(S\). Need to show \[\begin{align*} &(~ rnalen(\texttt{A}) \geq basecount(~(\texttt{A}, \texttt{A})~)~) \land (~ rnalen(\texttt{C}) \geq basecount(~(\texttt{C}, \texttt{A})~)~) \\ \land & (~ rnalen(\texttt{U}) \geq basecount(~(\texttt{U}, \texttt{A})~)~) \land (~ rnalen(\texttt{G}) \geq basecount(~(\texttt{G}, \texttt{A})~)~) \end{align*}\] We calculate, using the definitions of \(rnalen\) and \(basecount\):

Recursive Case: We will prove that \[\forall u \in S ~\forall b \in B ~( ~rnalen(u) \geq basecount(~(u, \texttt{A})~) \to rnalen(ub) \geq basecount(~(ub, \texttt{A})~)\]

Consider arbitrary RNA strand \(u\) and arbitrary base \(b\). Assume, as the induction hypothesis, that \(rnalen(u) \geq basecount(~(u,\texttt{A})~)\). We need to show that \(rnalen(ub) \geq basecount(~(ub, \texttt{A})~)\).

Using the recursive step in the definition of the function \(rnalen\): \[rnalen(ub) = 1 + rnalen(u)\] The recursive step in the definition of the function \(basecount\) has two cases. We notice that \(b = \texttt{A}\lor b \neq \texttt{A}\) and we proceed by cases.

Case i. Assume \(b = \texttt{A}\).

Using the first case in the recursive step in the definition of the function \(basecount\): \[basecount(~(ub, \texttt{A})~) = 1 + basecount(~(u,\texttt{A})~)\] By the induction hypothesis, we know that \(basecount(~(u,\texttt{A})~) \leq rnalen(u)\) so: \[basecount(~(ub, \texttt{A})~) = 1 + basecount(~(u,\texttt{A})~) \leq 1 + rnalen(u) = rnalen (ub)\] and, thus, \(basecount(~(ub,\texttt{A})~) \leq rnalen(ub)\), as required.

Case ii. Assume \(b \neq \texttt{A}\).

Using the second case in the recursive step in the definition of the function \(basecount\): \[basecount(~(ub, \texttt{A})~) = basecount(~(u,\texttt{A})~)\] By the induction hypothesis, we know that \(basecount(~(u,\texttt{A})~) \leq rnalen(u)\) so: \[basecount(~(ub, \texttt{A})~) = basecount(~(u,\texttt{A})~) \leq rnalen(u) < 1 + rnalen(u) = rnalen (ub)\] and, thus, \(basecount(~(ub,\texttt{A})~) \leq rnalen(ub)\), as required.

To organize our proofs, it’s useful to highlight which claims are most important for our overall goals. We use some terminology to describe different roles statements can have.

Theorem: Statement that can be shown to be true, usually an important one.

Less important theorems can be called proposition, fact, result, claim.

Lemma: A less important theorem that is useful in proving a theorem.

Corollary: A theorem that can be proved directly after another one has been proved, without needing a lot of extra work.

Invariant: A theorem that describes a property that is true about an algorithm or system no matter what inputs are used.

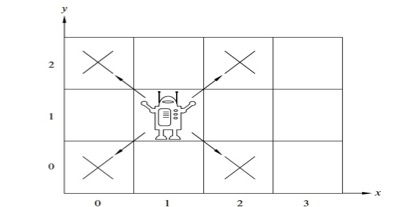

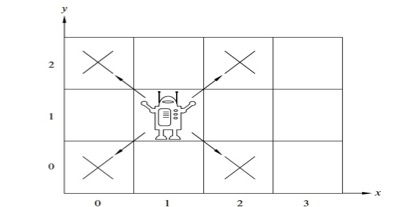

Theorem: A robot on an infinite 2-dimensional integer grid starts at \((0,0)\) and at each step moves to diagonally adjacent grid point. This robot can / cannot (circle one) reach \((1,0)\).

Definition The set of positions the robot can visit \(Pos\) is defined by: \[\begin{array}{ll} \textrm{Basis Step: } & (0,0) \in Pos \\ \textrm{Recursive Step: } & \textrm{If } (x,y) \in Pos \textrm{, then } \\ &\phantom{(x+1, y+1), (x+1, y-1), (x-1, y-1), (x-1, y+1)} \textrm{ are also in } Pos \end{array}\]

Example elements of \(Pos\) are:

Lemma: \(\forall (x,y) \in Pos~~( x+y \textrm{ is an even integer}~)\)

Why are we calling this a lemma?

Proof of theorem using lemma: To show is \((1,0) \notin Pos\). Rewriting the lemma to explicitly restrict the domain of the universal, we have \(\forall (x,y) ~(~ (x,y) \in Pos~~ \to ~~(x+y \textrm{ is an even integer})~)\). Since the universal is true, \((~ (1,0) \in Pos~~ \to ~~(1+0 \textrm{ is an even integer})~)\) is a true statement. Evaluating the conclusion of this conditional statement: By definition of long division, since \(1 = 0 \cdot 2 + 1\) (where \(0 \in \mathbb{Z}\) and \(1 \in \mathbb{Z}\) and \(0 \leq 1 < 2\) mean that \(0\) is the quotient and \(1\) is the remainder), \(1 ~\textrm{\bf mod}~ 2 = 1\) which is not \(0\) so the conclusion is false. A true conditional with a false conclusion must have a false hypothesis: \((1,0) \notin Pos\), QED. \(\square\)

Proof of lemma by structural induction:

Basis Step:

Recursive Step: Consider arbitrary \((x,y) \in Pos\). To show is: \[(x+y \text{ is an even integer}) \to (\text{sum of coordinates of next position is even integer})\] Assume as the induction hypothesis, IH that:

The set \(\mathbb{N}\) is recursively defined. Therefore, the function \(sumPow: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N}\) which computes, for input \(i\), the sum of the nonnegative powers of \(2\) up to and including exponent \(i\) is defined recursively by

\[\begin{alignat*} {2} \text{Basis step: } \qquad & sumPow(0) = 1 &\\ \text{Recursive step: } & \text{If } x \in \mathbb{N} \text{, then } &sumPow(x+1) = sumPow(x) + 2^{x+1} \end{alignat*}\]

\(sumPow(0) =\)

\(sumPow(1) =\)

\(sumPow(2) =\)

Fill in the blanks in the following proof of \[\forall n \in \mathbb{N}~(sumPow(n) = 2^{n+1} - 1)\]

Proof: Since \(\mathbb{N}\) is recursively defined, we proceed by .

Basis case: We need to show that . Evaluating each side: \(LHS = sumPow(0) = 1\) by the basis case in the recursive definition of \(sumPow\); \(RHS = 2^{0+1} - 1 = 2^1 - 1 = 2-1 = 1\). Since \(1=1\), the equality holds.

Recursive case: Consider arbitrary natural number \(n\) and assume, as the that \(sumPow(n) = 2^{n+1} - 1\). We need to show that . Evaluating each side: \[LHS = sumPow(n+1) \overset{\text{rec def}}{=} sumPow(n) + 2^{n+1}\overset{\text{IH}}{=} (2^{n+1} - 1) + 2^{n+1}.\] \[RHS = 2^{(n+1)+1}- 1 \overset{\text{exponent rules}}{=} 2 \cdot 2^{n+1} -1 = \left(2^{n+1} + 2^{n+1} \right) - 1 \overset{\text{regrouping}}{=} (2^{n+1} - 1) + 2^{n+1}\] Thus, \(LHS = RHS\). The structural induction is complete and we have proved the universal generalization. \(\square\)

Theorem: Every positive integer is a sum of (one or more) distinct powers of \(2\). Binary expansions exist!

The idea in the “Least significant first" algorithm for computing binary expansions is that the binary expansion of half a number becomes part of the binary expansion of the number of itself. We can use this idea in a proof by strong induction that binary expansions exist for all positive integers \(n\).

Proof by strong induction, with \(b=1\) and \(j=0\). We need to prove that for each positive integer \(n\), there is a positive integer \(k\) and coefficients \(a_0, \ldots, a_{k-1}\) where each \(a_i\) is \(0\) or \(1\) and \(a_{k-1} \neq 0\), and \[n = \sum_{i=1}^{k-1} a_i 2^i\]

Basis step: WTS property is true about \(1\).

Recursive step: Consider an arbitrary integer \(n \geq 1\).

Assume (as the strong induction hypothesis, IH) that the property is true about each of \(1, \ldots, n\).

WTS that the property is true about \(n+1\).

Idea: We will apply the IH to \((n+1) \textbf{ div } 2\).

Why is this ok?

Why is this helpful?

By the IH, we can write \((n+1) \textbf{ div } 2\) as a sum of powers of \(2\). In other words, there are values \(a_{k-1}, \ldots, a_0\) such that each \(a_i\) is \(0\) or \(1\), \(a_{k-1} = 1\), and \[\sum_{i=0}^{k-1} a_i 2^i = (n+1) \textbf{ div } 2\] Define the collection of coefficients \[c_{j} = \begin{cases} a_{j-1} \qquad&\text{if $1 \leq j \leq k$}\\ (n+1) \textbf{ mod } 2 &\text{if $j = 0$} \end{cases}\] Calculating: \[\begin{alignat*} {2} \sum_{j=0}^k c_j 2^j &= c_0 + \sum_{j=1}^k c_j 2^j = c_0 + \sum_{i=0}^{k-1} c_{i+1} 2^{i+1} &\qquad &\text{re-indexing the summation}\\ &= c_0 + 2 \cdot \sum_{i=0}^{k-1} c_{i+1}2^i &\qquad &\text{factoring out a $2$ from each term in the sum}\\ &= c_0 + 2 \cdot \sum_{i=0}^{k-1} a_{i} 2^i &\qquad &\text{by definition of $c_{i+1}$}\\ &= c_0 + 2 \left(~(n+1) \textbf{ div } 2 ~\right) &\qquad &\text{by IH} \\ &= \left(~ (n+1) \textbf{ mod } 2 ~\right ) + 2 \left(~(n+1) \textbf{ div } 2 ~\right) &\qquad &\text{by definition of $c_0$} \\ &= n+1 &\qquad&\text{by definition of long division} \end{alignat*}\]

Thus, \(n+1\) can be expressed as a sum of powers of \(2\), as required.

Theorem: Every positive integer greater than 1 is a product of (one or more) primes.

Before we prove, let’s try some examples:

\(20 =\)

\(100 =\)

\(5 =\)

Proof by strong induction, with \(b=2\) and \(j=0\).

Basis step: WTS property is true about \(2\).

Since \(2\) is itself prime, it is already written as a product of (one) prime.

Recursive step: Consider an arbitrary integer \(n \geq 2\). Assume (as the strong induction hypothesis, IH) that the property is true about each of \(2, \ldots, n\). WTS that the property is true about \(n+1\): We want to show that \(n+1\) can be written as a product of primes. Notice that \(n+1\) is itself prime or it is composite.

Case 1: assume \(n+1\) is prime and then immediately it is written as a product of (one) prime so we are done.

Case 2: assume that \(n+1\) is composite so there are integers \(x\) and \(y\) where \(n+1 = xy\) and each of them is between \(2\) and \(n\) (inclusive). Therefore, the induction hypothesis applies to each of \(x\) and \(y\) so each of these factors of \(n+1\) can be written as a product of primes. Multiplying these products together, we get a product of primes that gives \(n+1\), as required.

Since both cases give the necessary conclusion, the proof by cases for the recursive step is complete.

Suppose we had postage stamps worth \(5\) cents and \(3\) cents. Which number of cents can we form using these stamps? In other words, which postage can we pay?

\(11\)?

\(15\)?

\(4\)?

\[\begin{align*} &CanPay(0) \land \lnot CanPay(1) \land \lnot CanPay(2) \land \\ &CanPay(3) \land \lnot CanPay(4) \land CanPay(5) \land CanPay(6) \\ &\lnot CanPay(7) \land \forall n \in \mathbb{Z}^{\geq 8} CanPay(n) \end{align*}\]

where the predicate \(CanPay\) with domain \(\mathbb{N}\) is \[CanPay(n) = \exists x \in \mathbb{N} \exists y \in \mathbb{N} ( 5x+3y = n)\]

Proof (idea): First, explicitly give witnesses or general arguments for postages between \(0\) and \(7\). To prove the universal claim, we can use mathematical induction or strong induction.

Approach 1, mathematical induction: if we have stamps that add up to \(n\) cents, need to use them (and others) to give \(n+1\) cents. How do we get \(1\) cent with just \(3\)-cent and \(5\)-cent stamps?

Either take away a \(5\)-cent stamps and add two \(3\)-cent stamps,

or take away three \(3\)-cent stamps and add two \(5\)-cent stamps.

The details of this proof by mathematical induction are making sure we have enough stamps to use one of these approaches.

Approach 2, strong induction: assuming we know how to make postage for all smaller values (greater than or equal to \(8\)), when we need to make \(n+1\) cents, add one \(3\) cent stamp to however we make \((n+1) - 3\) cents.

The details of this proof by strong induction are making sure we stay in the domain of the universal when applying the induction hypothesis.